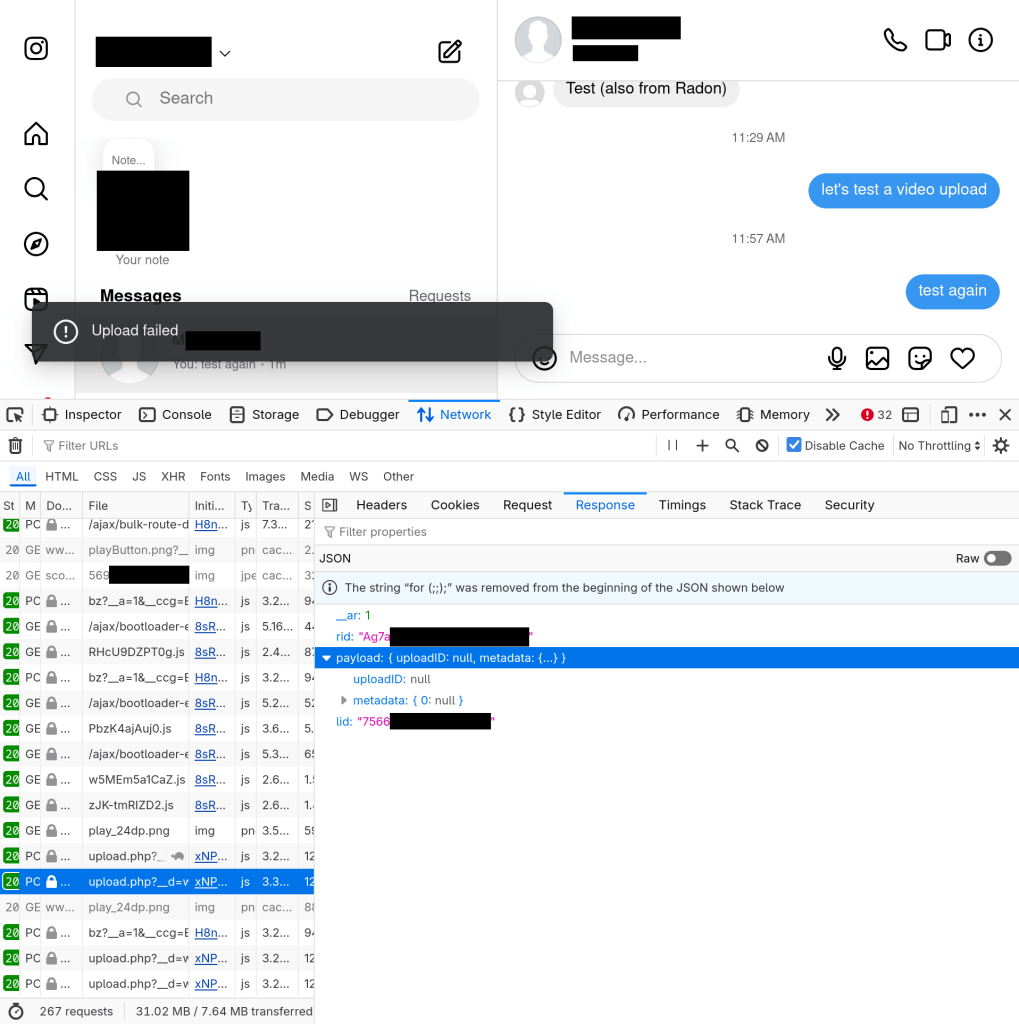

Beeper allows you to chat with people on a variety of platforms from a single app (with true end-to-end encryption through on-device connections). Recently, we started getting a lot of users saying they couldn’t send videos to people in their Instagram DMs. This was confusing, because at first we weren’t able to reproduce the same problem. However, after some investigation, we found a surprising fact: this was not a Beeper problem at all, but an Instagram one! For a certain subset of Instagram user accounts, all attempts to send a video attachment through the official https://www.instagram.com/direct/ web interface would simply fail, displaying a message saying “Upload failed” with no further details. Here is a screenshot from an affected user:

The reason this Instagram problem also affected Beeper users was simple: Beeper communicates with Instagram servers exactly the same way the official website does, so if the Instagram website stops working, Beeper’s Instagram connections will too.

However, since we don’t have a way to ask Meta to fix the problem, we needed to find a different way to get our users’ video uploads back online. After some further investigation, we noticed something interesting: the issue only affected video uploads through the Instagram web interface; uploads from the Instagram mobile apps were not broken. Was it possible for Beeper to use the same method as the Instagram mobile app in order to work around the problem?

I decided to explore this possibility, starting with Instagram on Android. Using a bootloader-unlocked Google Pixel 7 test device with LineageOS and KernelSU installed, I set up my reverse engineering tools for inspecting the network traffic sent by Instagram. Using an operating system that supports root access is a must for both reverse engineering and privacy, interests which often go hand in hand: otherwise, vendors like Google and Samsung block you from seeing what data your (and their) own apps are sending up to third parties. Network traffic inspection is a common tool for privacy analysts and consumer rights advocates.

There are many ways to inspect the behavior of a mobile app, but one of the most common is mitmproxy. You run the proxy on your computer, install the proxy CA certificate on your phone to tell it to trust your proxy with decrypting the data you send through it, and configure your wi-fi settings to direct outgoing connections from your phone through your laptop. Or, that’s how it should work, but…

… unfortunately, device manufacturers and app developers work together to prevent your preferred privacy settings from applying to their apps. For one thing, installing a custom CA certificate on Android does almost nothing, because it isn’t actually used for certificate validation unless an app specifically opts in to respecting user configuration. That problem can be worked around using the KernelSU module AlwaysTrustUserCerts. However, companies like Meta often include custom code inside their apps to block the usage of any certificate validation that is not approved by the company. So, in order to inspect Instagram network traffic, some further investigation was required.

My tool of choice for manipulating the runtime behavior of Android apps is Frida, which can be installed on the phone using the KernelSU module magisk-frida (or via alternative solutions such as patching individual apps using Apktool and/or Objection, but these tend to be trickier). Frida allows you to attach directly to a process running on your phone and both inspect and modify what’s happening at the code level – including things like substituting in your own versions of internal functions to see how app behavior might change.

There are plenty of freely available Frida scripts for undoing the kind of restrictions often applied to Android and iOS apps, like for example this popular project for Instagram by developer Eltion. However, obfuscation techniques used by app developers evolve continuously, so what’s available online may no longer work. In my testing, the latest Frida script by Eltion was able to bypass Meta’s restrictions for some network requests, but not all of them. As a result, I needed to develop my own solution. Let me walk you through the process.

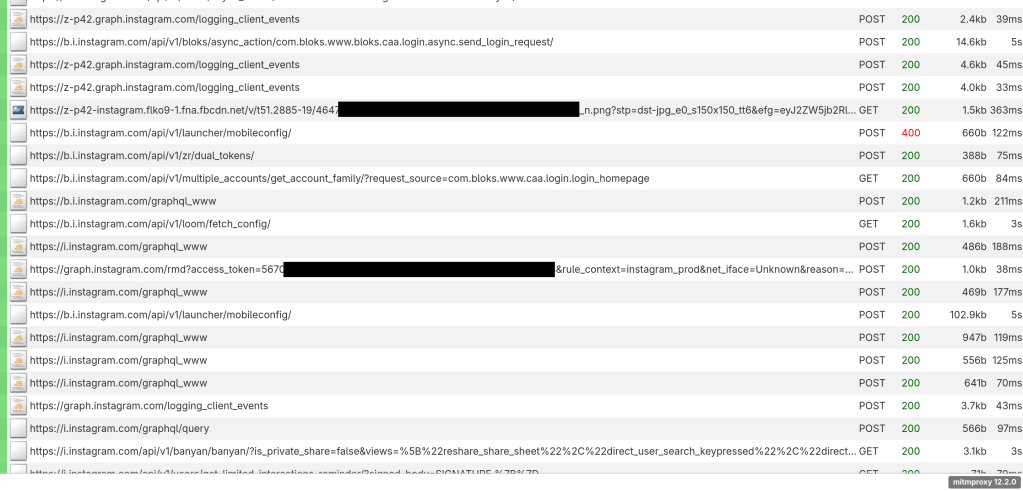

I start by establishing a test procedure. I found that when I started the Instagram app from a clean state, with user storage cleared, it started by making a number of requests to b.i.instagram.com and z-p42.graph.instagram.com, which were aborted because code inside the Instagram app detected that mitmproxy was being used to inspect traffic. My goal was to determine what was causing these requests to be aborted, and then to disable that logic.

To find a place to start, I decompiled the Instagram app with Apktool and searched for relevant-seeming strings like certificate and pinning (as the practice of ignoring user-configured certificate trust settings is often called certificate pinning). One likely candidate appeared in the obfuscated Java class X/3kp, which had been decompiled by Apktool from Java bytecode to Smali assembly language:

smali/X/3kp.smali

1048: const-string v0, "\\n Peer certificate chain:"

1135: const-string v0, "\\n Pinned certificates for "

Unfortunately, the code is fairly obfuscated even in decompiled form, which makes it difficult to tell if this is even the right place to intercept. Simple string-based search like this is usually helpful in gaining inspiration. In this case, inspiration came from the following two lines:

.catch Ljava/security/cert/CertificateException; {:try_start_1 .. :try_end_1} :catch_0

.catch Ljavax/net/ssl/SSLPeerUnverifiedException; {:try_start_1 .. :try_end_1} :catch_1

In Java, most methods report errors by raising exceptions. It follows that if a network library were to fail certificate validation and abort a connection, it’s likely that a certificate-related exception would be thrown. But with Frida, we can actually edit the behavior of the Exception constructor to report exactly what exceptions are being thrown, and from where. This can help to produce a much more accurate story about how the certificate pinning logic might be implemented.

Based on the Frida JavaScript API documentation and other examples available online, here is a simple Frida script that will log whenever the two Exception constructors above are called:

Java.perform(() => {

for (const clsname of [

"java.security.cert.CertificateException",

"javax.net.ssl.SSLPeerUnverifiedException",

]) {

const Exception = Java.use(clsname);

for (const overload of Exception.$init.overloads) {

overload.implementation = function (...args) {

console.log(`Instagram wants to throw an exception: ${Exception} ${args}`);

overload.call(this, ...args);

};

}

}

}

Repeating the test, but using Frida to launch and immediately attach to the Instagram app process via frida -U -f com.instagram.android -l logexceptions.js, we get a lot of logs like this when the app starts up:

Instagram wants to throw an exception <class: java.security.cert.CertificateException> pinning error: certificate chain empty

Seems promising. But we are too late: by the time the CertificateException constructor is called, the app has already realized that something is amiss, and there’s not much we can do at that point to get things back on track. Luckily, with the full power of an attached Frida session, we can easily print a stack trace at the exact point the CertificateException is created, which will tell us what code path brought us there. Here’s the resulting trace:

java.security.cert.CertificateException: pinning error: certificate chain empty

at X.0LA.A00(:131)

at X.0Kz.AJR(:10)

at X.OD7.AJR(:10)

at com.facebook.mobilenetwork.internal.certificateverifier.CertificateVerifier.verify(:537019859)

at com.facebook.mobilenetwork.internal.certificateverifier.CertificateVerifier.verify(:268435460)

at com.facebook.tigon.tigonmns.TigonMNSServiceHolder.runEVLoop(Native Method)

at com.facebook.tigon.tigonmns.TigonMNSServiceHolder.access$runEVLoop(:0)

at X.3ni.run(:2)

at X.3no.run(:17)

at java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:1119)

By stepping a few stack frames up, we arrive at the very suspicious-sounding CertificateVerifier.verify. This seems like a great candidate to modify. What if we simply replace the implementation with one that returns immediately without throwing an exception? This is straightforward to test:

Java.perform(() => {

const CertificateVerifier = Java.use(

"com.facebook.mobilenetwork.internal.certificateverifier.CertificateVerifier",

);

for (const overload of CertificateVerifier.verify.overloads) {

overload.implementation = () => {

console.log(`Instagram wants to verify a certificate; skipping it`);

};

}

});

When combining this patch with the existing patches provided by Eltion, all requests made by the Instagram app on Android can be successfully decrypted by mitmproxy:

Now, of course these Frida patches do not fix the certificate validation in the Instagram app (i.e., making it respect the network settings you’ve configured in the operating system). Instead, they do the simpler task of completely disabling certificate validation. So this is not something that would be acceptable to use on a public wi-fi network or with an important Instagram account, as it would allow other people on the same network to access your credentials. Instead, we can use it as a temporary way (in a trusted environment) to get insight into how the app functions, so that we can implement a more robust solution that will be secure and production-ready.

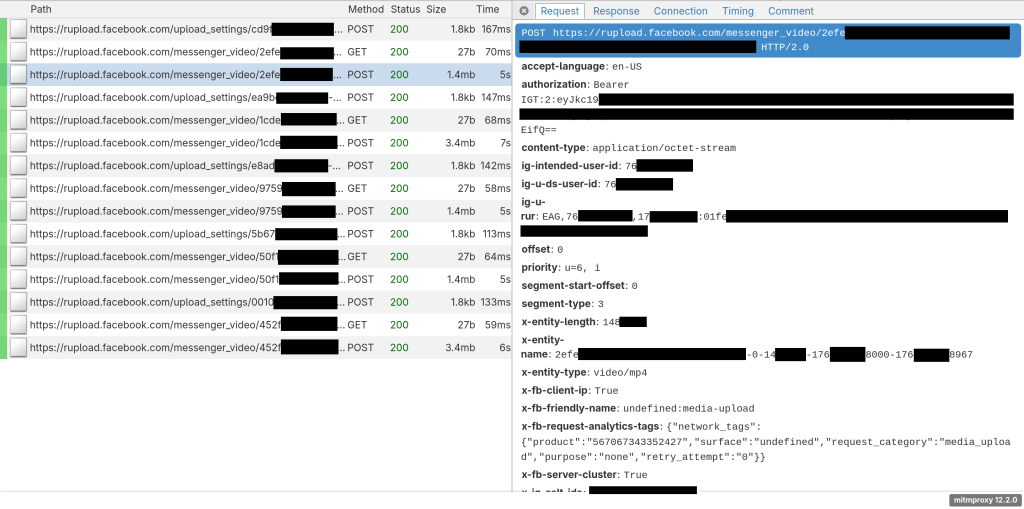

Now, how does the uploading work? When sending a video attachment through the Android app, three requests show up in mitmproxy, all to rupload.facebook.com. The third one seems the most important, as it includes the actual video file as an HTTP POST body:

I’ve written in the past about taking a network request and making repeated changes to it as a way of narrowing down which parameters are required and validating your approach to choosing the right ones. By starting with the “Copy as cURL” option in mitmproxy and then testing various parameter options, we found the following:

- If the

authorizationheader is missing, then the request returns an HTTP 400 errorUser not authorized to perform this request. The same happens if theuser-agentheader isn’t set to one that matches what Instagram expects. - The

x-entity-nameheader (which matches the parameter aftermessenger_video/in the URL) must be changed to a new value for each upload, as otherwise a cached result from the previous upload will be returned. - The

ig-u-ds-user-id,offset, andvideo_typeheaders are required. Note that one of these randomly has an underscore instead of using hyphens like the rest. It’s easy to get tripped up by tiny details like that!

Now, the biggest open question here is: can we even use this HTTP endpoint from our existing code, which is otherwise written against the Instagram web API? It’s possible that they use completely different authentication schemes, and so we wouldn’t be able to use existing credentials in the Beeper Instagram connection to make requests against the Android API.

So, with some trepidation, I inspected the structure of the authorization header. In a stroke of luck, however, this header was trivial to synthesize out of the existing web API credentials. You simply take the ds_user_id and sessionid cookies, pack them into a JSON object, serialize it into base64, and prefix with Bearer IGT:2:. I don’t know whether the Android app does this same synthesis, or whether it receives the pre-packaged token from the server – but fortunately, I don’t need to know in order to replicate the behavior!

By comparing multiple subsequent requests, I made educated guesses on how to generate the variable parameters:

- The

ig-u-ds-user-idis the Instagram user ID for the account you’re logged in as, which is already available as theds_user_id. - The

x-entity-nameappears to be arbitrary, but we wanted to match the format used by the official Android app. The first component is a random hex string, followed by a zero, followed by the length of the video file being uploaded, followed by the UNIX timestamp in milliseconds rounded to the nearest second, followed by the UNIX timestamp in milliseconds not rounded to the nearest second(?!).

After some testing, the new request style appeared to be working! However, it’s not ideal to be using two different client APIs at the same time (both web and Android), so we opted to minimize impact by only falling back to the Android endpoint for video uploads when we get the specific error that indicates the web API is broken for the current Instagram account.

Because Beeper bridges are open-source (and can be self-hosted), you can see the full code necessary to implement this workaround for Instagram connections, publicly on GitHub: https://github.com/mautrix/meta/pull/167/files. I think it’s very cool that we’re able to provide working chat features back to users even when they’ve become unavailable on the underlying network, as in this case where Instagram video uploads on web stopped working.

Radon